Back again with the next part of the series. We start off by getting into the short-term debt cycle, continuing down the road we began last week.

Short Term Debt Cycle

When fueled by credit, both spending and prices begin to rise. Since credit can be created out of thin air, this helps create the first phase of the short term debt cycle, expansion.

When spending and incomes grow faster than the production of goods, prices rise. When prices rise, we call this inflation.

Too much inflation causes problems, so the central bank will raise interest rates to discourage additional borrowing.

But what does this do?

As we’ve covered before, one person’s spending is another person’s income. So if the central bank is raising the price of credit, some people will be unable to afford it. This gives them less money to spend, which means less income for other people. In addition to income, prices go down, which is called deflation.

If incomes fall too far, people will be unable to afford the debt they have already acquired. This leads to defaulting on debts, and brings us to a recession. If the recession is severe enough, the central bank lowers interest rates, making credit more affordable.

This starts the cycle all over again.

In essence, for the short term debt cycle, spending is only constrained by the willingness of the lenders and borrowers to provide and receive credit. When credit is easily available there is an economic expansion. When credit isn’t easily available there is a recession.

Note that this process is controlled mainly by the central bank. Also note what happens following each short term debt cycle.

The top and bottom of each cycle finish with more growth than the previous cycle, and with more debt.

Why does this happen? Human nature…

People have an inclination to borrow and spend more instead of paying back debt. Because of this, over a long period of time, debts rise faster than incomes which creates…

The Long Term Debt Cycle

Despite borrowers being overextended by debt, lenders will continue to provide credit. People tend to focus just on what’s happening lately. And what’s been happening lately? Incomes are rising, asset values are going up, the stock market roars. It’s a boom!

It pays to buy goods, services, and financial assets with borrowed money. When people do a lot of that, we call it a bubble.

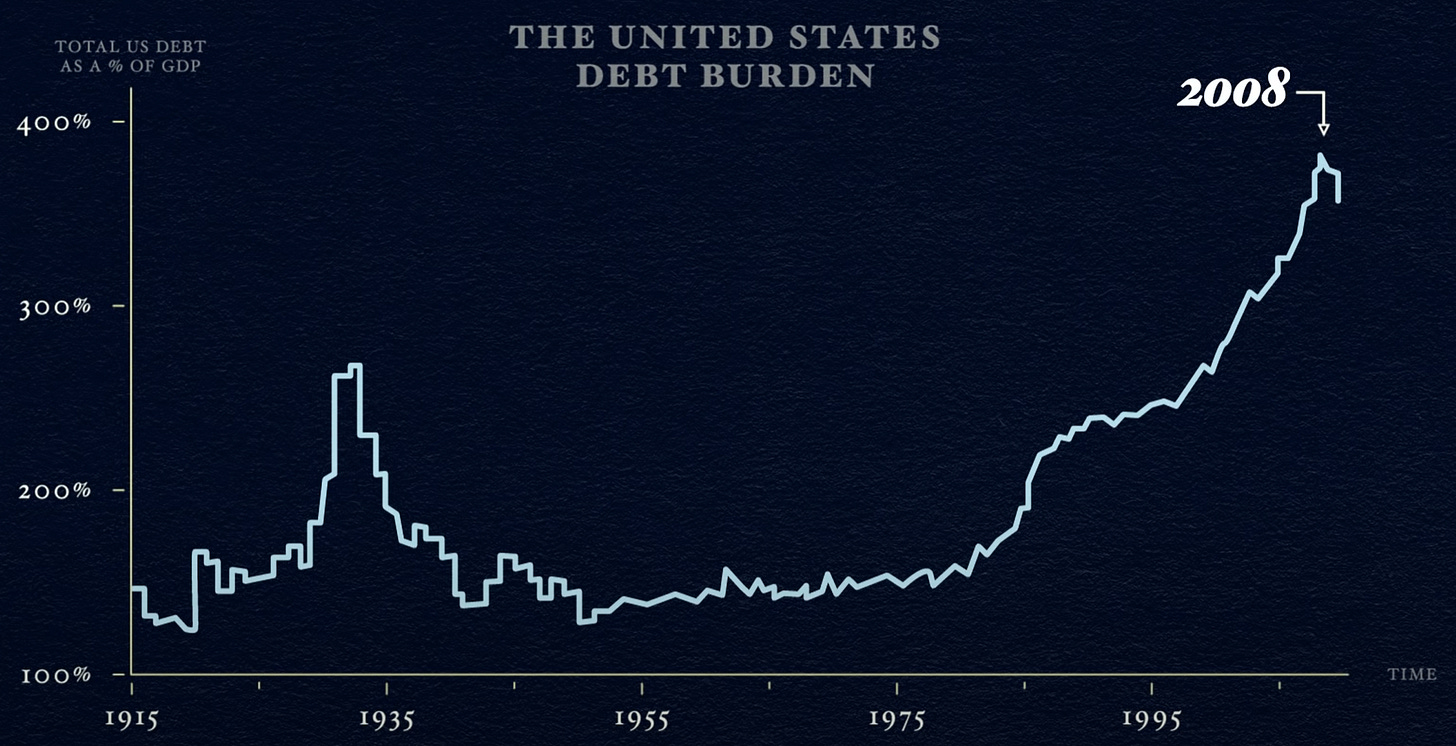

And even though debts have been growing, incomes have been growing nearly as fast to offset them. We call the ratio of debt-to-income the debt burden. So long as incomes continue to rise, the debt burden remains manageable.

So even though credit is rising, incomes and asset prices rise enough to keep borrowers credit-worthy for a long time.

But this obviously cannot go on forever. At some point, debt repayments start to grow faster than incomes, forcing people to cut back on their spending. We saw this play out above in the short term debt cycle, leading to recession.

So what happens when this plays out in the long term debt cycle?

For the United States, and much of the world, 2008 was the last time we faced a debt burden peak.

This peak leads to a deleveraging where people cut spending, incomes fall, credit disappears asset prices drop, banks get squeezed, the stock market collapses, social tensions rise, and the whole thing starts to feed on itself the other way.

It becomes a self-reinforcing pattern.

Since incomes have fallen, people sell assets to pay debts. But since everyone is rushing to sell at the same time, prices drop. With falling incomes and asset prices, borrowers are less credit-worthy, giving them less to spend. As people have less available to spend, incomes continue to fall. So on and so forth.

This looks similar to a recession, but the difference is that interest rates cannot be lowered to save the day. In a deleveraging, interest rates are already low and soon hit 0%.

As we see, interest rates hit 0% in the deleveraging of the 1930s and again in 2008. This, essentially, causes the entire economy to be not credit-worthy.

So what do we do about a deleveraging to get things moving again?

The problem is that debt burdens are too high and must come down. There are 4 ways this can happen:

Cut Spending

Reduce Debt

Redistribute Wealth

Print Money

We’ll be getting into these 4 strategies next week.