Back with the final part of Markets and Money. Next week I’ll consolidate all 4 down to one final lesson.

4 Strategies for a Deleveraging

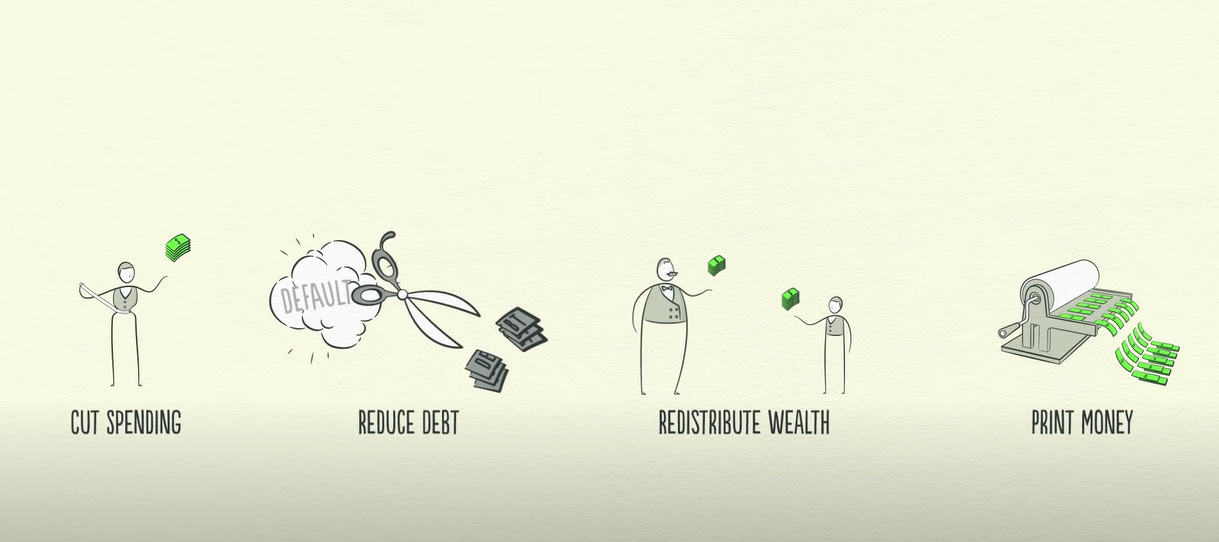

As discussed last week, there are 4 strategies that have happened in every deleveraging in modern history:

Usually, spending is cut first. From individuals to governments, everyone tightens their belts and cuts spending to pay down their debt. This is referred to as austerity.

You might expect that this process will decrease the debt burden, but the opposite is actually true. Incomes fall along with spending, and they fall faster than debts are being repaid. This makes the debt burden get worse!

This leads to the next step, reducing debt.

A borrower’s debts are a lender’s assets. When the borrower doesn’t repay the bank, people get nervous that the bank won’t be able to repay them, so they rush to withdraw their money from the bank. Banks get squeezed, and people, businesses, and banks default on their debts.

This contraction is called a depression. A big part of a depression is people discovering much of what they thought was their wealth isn’t really there.

Remember the bar tab scenario? If you open a bar tab, you’ve got a liability and the bartender has an asset. But if you default on the debt (skip out on paying) the bartender’s asset disappears.

Many lenders don’t want their assets to disappear, so they agree to a debt restructuring. This means lenders get paid back less, or over a longer period of time, or for a lower interest rate, etc. Lenders would rather have a little of something rather than a lot of nothing.

Even though debt disappears, it causes income and asset values to disappear faster, so the debt burden continues getting worse. All of this impacts the central government, because lower incomes and less employment means the government collects fewer taxes.

At the same time, it needs to increase its spending because unemployment has risen. Many of the unemployed and inadequate savings and need assistance from the government. Additionally, governments create stimulus plans and increase their spending to make up for the decrease in the economy.

Government’s budget deficits explode in a deleveraging because they spend more than they earn in taxes.

To raise money, governments need to either raise taxes or borrow money. But with incomes falling and unemployment rising, who is the income going to come from? The Rich. Since a large amount of wealth tends to accumulate in a small number of hands, governments raise taxes on the wealthy.

This facilitates the next step, redistribution of wealth.

The “have-nots” who are suffering begin to resent the wealthy. The wealthy “haves” begin feeling squeezed by the weak economy and higher taxes begin to resent the “have-nots".

If the depression continues, social disorder can breakout.

Not only do tensions rise within countries, but they can rise between countries. In the 1930s this led to Hitler coming to power, war in Europe, and depression in the United States.

Remember, most of what people thought was money was credit. So when credit disappears, people don’t have enough money. People are desperate for money.

This gives us our final step, printing money.

Unlike the first 3 steps, printing money is inflationary and stimulative. The central bank makes money out of thin air and uses it to buy financial assets and government bonds.

By buying financial assets with this money, it helps to drive the prices of assets up, which makes people more creditworthy. However, this only helps people with financial assets.

The central government, on the other hand, can buy goods and services which puts money into the hands of the people, but it can’t print money. So in order to stimulate the economy, the central bank and central government must cooperate.

By purchasing government bonds, the central bank essentially lends money to the central government, allowing it to run a deficit and increase spending on goods and services through its stimulus programs and on unemployment benefits.

This increases people’s income and also increases government debt. However, it will lower the economy’s total debt burden. This is a very risky time.

Policymakers need to balance the 4 ways that debt burdens come down. The deflationary ways need to balance with the inflationary ways in order to maintain stability. If balanced correctly, there can be a beautiful deleveraging.

How can a deleveraging be beautiful?

Even though a deleveraging is a difficult situation, handling a difficult situation in the best possible way is beautiful. A lot more beautiful than the debt-fueled excesses of the leveraging phase.

In a beautiful deleveraging, debts decline relative to income, real economic growth is positive, and inflation isn’t a problem.

A dollar of spending paid for with money has the same effect as a dollar of money paid for with credit. By printing money, the central bank can make up for the disappearance in credit with an increase in the amount of money.

In order to turn things around, the central bank needs to not only pump up income growth but get the rate of income growth higher than the rate of interest on the accumulated debt.

Basically, income needs to grow faster than debt grows.

Let’s imagine a 1:1 debt to income ratio. We have the same amount of debt as money in circulation. If the interest rate on that debt is 2% and income is only growing at 1% you will never pay back the debt. The central bank would need to print enough money to get the rate of income growth higher than the interest on the debt.

However, printing money can easily be abused because it’s so easy to do and people prefer it to the alternatives. The key is to avoid printing too much money and causing unacceptably high inflation, the way Germany did in the 1920s.

When policymakers balance all 4 strategies, that is a beautiful deleveraging. Growth is slow, but debt burdens go down.

When incomes begin to rise, borrowers become more creditworthy. And when borrowers begin more creditworthy we see the cycle start all over again.

It takes roughly a decade for the deleveraging process to finish, which is where the term lost decade comes from.

In Closing

Obviously, the economy is a bit more complicated than this template suggests. However, laying the short-term debt cycle on top of the long-term debt cycle, and then laying both of them on top of the productivity growth line, gives a reasonably good template for where we’ve been, where we are now, and where we’re headed.

There are 3 rules of thumb that I’d like you to take away from this.

Don’t have debt rise faster than income.

Don’t have income rise faster than productivity.

Do all that you can to raise your productivity.