My consolidated summary that covers the entirety of the 31-minute video, How The Economic Machine Works by Ray Dalio.

I take Dalio’s words directly from the video and slice them up a bit to make an easy to follow guide on understanding the economy… Hopefully, at least.

If you’d like even more details, check out the entire series.

The Basics

An economy is simply the sum of the transactions that make it up. All forces within the economy are driven by transactions, so if we can understand transactions, we can understand the whole economy.

A market consists of all the buyers and all the sellers making transactions for the same thing. For example, there is a wheat market, car market, housing market, etc.

The economy consists of all of the transactions in all of its markets. If you add up the total spending and total quantity sold in all of the markets, you have everything you need to know to understand the economy.

The main players in the economy are:

People

Businesses

Banks

Governments

The biggest buyer and seller is The Government, which consists of two important parts.

Central Government - collects taxes and spends money

Central Bank - controls the amount of money and credit in the economy.

This is done by influencing interest rates and printing money.

Credit (debt) is the most important part of the economy because it is the biggest and most volatile.

When interest rates are high, there is less borrowing because it is too expensive. When interest rates are low, borrowing increases because it's cheaper. When borrowers agree to repay, and lenders believe them, credit is created.

Debt is both an asset to the lender and a liability to the borrower. Once the debt is repaid, the asset and liability disappear and the transaction is settled.

This brings us to the biggest lesson so far:

When a borrower receives the credit he is able to increase his spending. And spending drives the economy. This is because one person's spending is another person's income.

In simple terms, it works like this…

The boost to income provides a boost to borrowing. The boost in borrowing provides a boost to spending. The boost in spending provides a boost in productivity. The boost in productivity provides a boost to income. So on and so forth.

And since one person's spending is another person's income, it creates an environment for growth.

Cycles

In a transaction, you have to give something in order to get something, and how much you get depends on how much you produce. Over time, we learn, and that accumulated knowledge raises our living standards.

We call this productivity growth.

Productivity growth doesn’t fluctuate much, so it’s not a big driver of economic swings. Instead, debt is, because it allows us to consume more than we produce when we acquire it, and it forces us to consume less than we produce when we pay it back.

This brings us to the 3 Main components of the economy:

Productivity Growth

Short Term Debt Cycle (5-8 years)

Long Term Debt Cycle (75-100 years)

While most people feel the swings, they don’t typically see them as cycles. They seem them too up-close - day by day, week by week.

Let’s, for a second, imagine an economy without credit.

In this economy, the only way I can increase my spending is to increase my income, which requires me to be more productive and do more work. Increased productivity is the only way for growth.

But because we borrow (going back to our economy) we have cycles. This isn’t due to any laws or regulations, it’s due to human nature and the way that credit works.

Think of borrowing as a way of pulling spending forward. In order to buy something you can’t afford, you need to spend more than you make. To do this you need to borrow from your future self.

Basically… Anytime you borrow, you create a cycle. This is as true for an individual as it is for the economy. This is why understanding credit is so important because it sets into motion a mechanical and predictable series of events that will happen in the future.

This makes credit different from money.

Money is what you settle a transaction with. If you buy a beer from a bartender with cash, the transaction is settled immediately. But when you buy a beer with credit, it’s like starting a bar tab.

Together, you and the bartender create an asset and liability. The reality is, what most people call money, is actually credit.

The total amount of credit in the United States is about $50 trillion, and the total amount of money is only about $3 trillion. (These numbers have surely changed since this video was first released.)

In an economy with credit, we can follow the transactions and see how credit creates growth. Let me give you an example.

Suppose you earn $100k a year and have no debt. You’re creditworthy enough to borrow $10k, allowing you to spend $110k, even though you only earn $100k.

Since your spending is another person’s income, someone is earning $110k. The person earning $110k, with no debt, can borrow $11,000. This allows spending of $121k.

His spending is another person’s income, and by following the transaction, we can begin to see how this process works in a self-reinforcing pattern.

But remember, borrowing creates cycles, and if the cycle goes up, it eventually needs to come down.

Short Term Debt Cycle

When fueled by credit, both spending and prices begin to rise. Since credit can be created out of thin air, this helps create the first phase of the Short Term Debt Cycle, expansion.

When spending and incomes grow faster than the production of goods, prices rise. When prices rise, we call this inflation.

Too much inflation causes problems, so the central bank will raise interest rates to discourage additional borrowing.

As we’ve covered before, one person’s spending is another person’s income. So if the central bank is raising the price of credit, some people will be unable to afford it. This gives them less money to spend, which means less income for other people. In addition to income, prices go down, which is called deflation.

This leads to defaulting on debts, and brings us to a recession. If the recession is severe enough, the central bank lowers interest rates, making credit more affordable.

This starts the cycle all over again.

Note that this process is controlled mainly by the central bank. Also note what happens following each short term debt cycle.

The top and bottom of each cycle finish with more growth than the previous cycle, and with more debt.

Why does this happen? Human nature… People have an inclination to borrow and spend more instead of paying back debt.

Long Term Debt Cycle

Despite borrowers being overextended by debt, lenders will continue to provide credit. People tend to focus just on what’s happening lately. And what’s been happening lately? Incomes are rising, asset values are going up, the stock market roars. It’s a boom!

It pays to buy goods, services, and financial assets with borrowed money. When people do a lot of that, we call it a bubble.

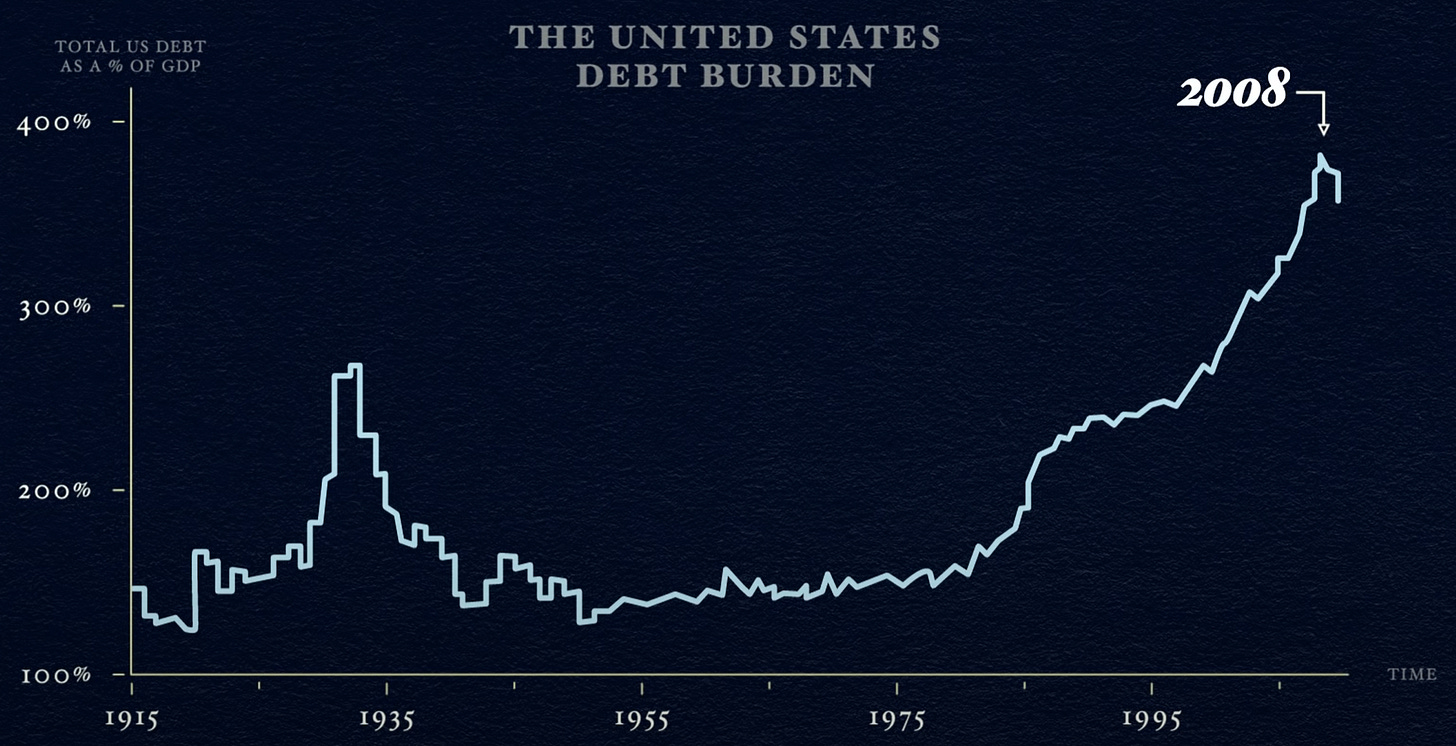

And even though debts have been growing, incomes have been growing nearly as fast to offset them. We call the ratio of debt-to-income the debt burden. So long as incomes continue to rise, the debt burden remains manageable.

So what happens when this plays out in the long term debt cycle?

For the United States, and much of the world, 2008 was the last time we faced a debt burden peak.

This peak leads to a deleveraging where people cut spending, incomes fall, credit disappears asset prices drop, banks get squeezed, the stock market collapses, social tensions rise, and the whole thing starts to feed on itself the other way.

Since incomes have fallen, people sell assets to pay debts. But since everyone is rushing to sell at the same time, prices drop. With falling incomes and asset prices, borrowers are less credit-worthy, giving them less to spend. As people have less available to spend, incomes continue to fall. So on and so forth.

This looks similar to a recession, but the difference is that interest rates cannot be lowered to save the day. In a deleveraging, interest rates are already low and soon hit 0%.

As we see, interest rates hit 0% in the deleveraging of the 1930s and again in 2008. This, essentially, causes the entire economy to be not credit-worthy.

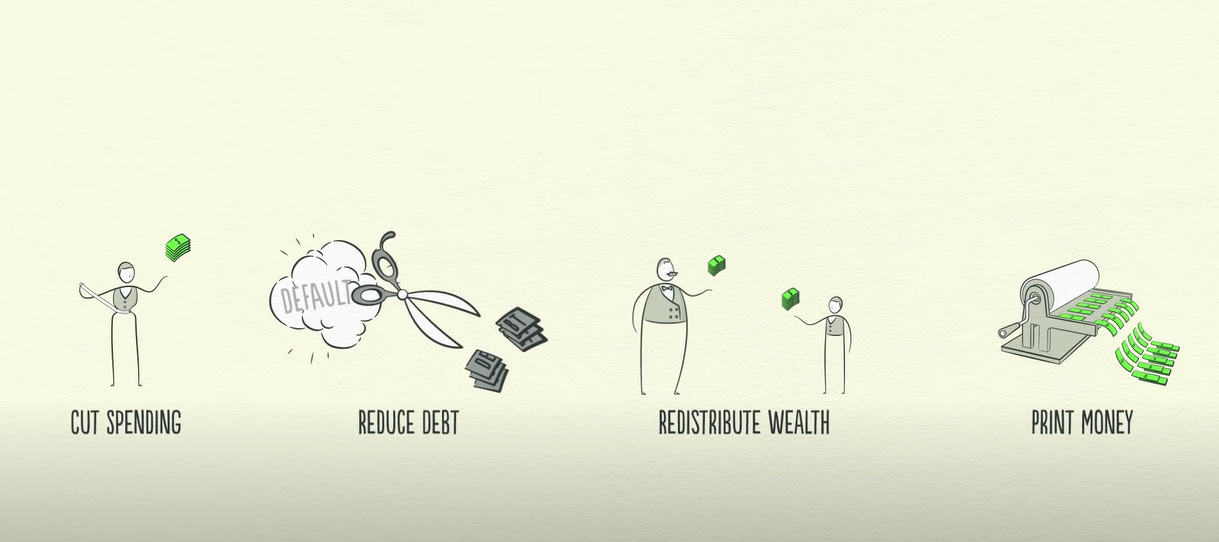

The problem is that debt burdens are too high and must come down. There are 4 ways this can happen:

Cut Spending

Reduce Debt

Redistribute Wealth

Print Money

Deleveraging

Usually, spending is cut first. From individuals to governments, everyone tightens their belts and cuts spending to pay down their debt. This is referred to as austerity.

You might expect that this process will decrease the debt burden, but the opposite is actually true. Incomes fall along with spending, and they fall faster than debts are being repaid. This makes the debt burden get worse!

This leads to the next step, reducing debt.

A borrower’s debts are a lender’s assets. When the borrower doesn’t repay the bank, banks get squeezed, and people, businesses, and banks default on their debts.

This contraction is called a depression. A big part of a depression is people discovering much of what they thought was their wealth isn’t really there.

Many lenders don’t want their assets to disappear, so they agree to a debt restructuring. Lenders would rather have a little of something rather than a lot of nothing.

Even though debt disappears, it causes income and asset values to disappear faster, so the debt burden continues getting worse.

Government’s budget deficits explode in a deleveraging. Less income means less taxes, and more unemployment means more assistance. To raise money, governments need to either raise taxes or borrow money. But with incomes falling and unemployment rising, who is the income going to come from? The Rich.

This facilitates the next step, redistribution of wealth.

The “have-nots” who are suffering begin to resent the wealthy. The wealthy “haves” begin feeling squeezed by the weak economy and higher taxes begin to resent the “have-nots".

If the depression continues, social disorder can breakout. Remember, most of what people thought was money was credit. So when credit disappears, people don’t have enough money. People are desperate for money.

This gives us our final step, printing money.

Unlike the first 3 steps, printing money is inflationary and stimulative. The central bank makes money out of thin air and uses it to buy financial assets and government bonds.

By buying financial assets with this money, it helps to drive the prices of assets up, which makes people more creditworthy. However, this only helps people with financial assets.

The central government, on the other hand, can buy goods and services which puts money into the hands of the people, but it can’t print money. So in order to stimulate the economy, the central bank and central government must cooperate.

By purchasing government bonds, the central bank essentially lends money to the central government, allowing it to run a deficit and increase spending on goods and services through its stimulus programs and on unemployment benefits.

This is a very risky time.

Policymakers need to balance the 4 ways that debt burdens come down. The deflationary ways need to balance with the inflationary ways in order to maintain stability.

In order to turn things around, the central bank needs to not only pump up income growth but get the rate of income growth higher than the rate of interest on the accumulated debt.

Basically, income needs to grow faster than debt grows.

However, printing money can easily be abused because it’s so easy to do and people prefer it to the alternatives. The key is to avoid printing too much money and causing unacceptably high inflation, the way Germany did in the 1920s.

It takes roughly a decade for the deleveraging process to finish, which is where the term lost decade comes from.

That’s it! That’s the economy in a nutshell. Understanding this will help us understand where we are in the current debt cycle.

Unfortunately, the deleveraging that was supposed to happen in 2008 was pushed back. The Fed continued to push down interest rates and printed money to bail out failing institutions.

The debt burden has continued to grow, and we appear to be in a printing frenzy. At the same time, wealth has not sufficiently been redistributed, helping to lead to rising social unrest.

TO close out, I’ll leave you with the 3 rules of thumb that Dalio would like us to take away from the video.

Don’t have debt rise faster than income.

Don’t have income rise faster than productivity.

Do all that you can to raise your productivity.